Drawing on the expertise of our partners around the world, Agacad is currently examining the specific situation of BIM use in different countries.

Here we look at Norway with the help of Knut Sandvik, a construction engineer and IT professional with three decades of experience who works at Focus Software AS, Norway’s top provider of BIM solutions. Knut also teaches BIM at the university level.

Early adopter

Norway today is one of the world’s most advanced countries in BIM implementation. One reason is how early the government got involved in promoting digital construction. Statsbygg, the Norwegian Directorate of Public Construction and Property, ran a BIM pilot project in 2005, published a BIM manual in 2008, and began requiring BIM use in public projects already in 2010.

“Finland was the first to have a government BIM mandate and then Norway and some other countries were second,” Knut Sandvik says. “The Norwegian state has been requiring the use of BIM for over a decade now, so everyone involved in big projects – hospitals, airports, operas and the like – has been doing BIM to one degree or another for quite some time now.”

Besides that top-down encouragement, Norway has also seen grassroots movement to BIM among designers, owners and builders. Sandvik says BIM adoption, while far from universal, is extensive and continues increasing: “You have all kinds of approaches to BIM, how to use it and how much, even when it’s not required. Almost everybody now uses BIM modelling tools – maybe not the methods, but the tools yes, and over time it is slowly seeping into their methods too.”

The makers and sellers of those tools for BIM have been key drivers of BIM advances.

“At Focus Software, we have a large customer base and we are always doing education, also at universities. We work to educate our customer base, and our competitors do the same,” Sandvik notes. Studies for AEC professionals that cover technical (not just artistic) matters, are often quite good at teaching BIM tools and methods, he says.

High-end BIM standard

Over the years, Norway’s government (Statsbygg, to be precise) has developed a BIM standard, known as SIMBA, which must be used for public buildings.

“It’s a well-established standard, used quite a lot, though it’s quite high-end. Many builders, when they aren’t required to use it, take a more hands-on approach to standardization,” Sandvik says. The European BIM standard, CEN/TC 442, is starting to be required for projects in Norway too, he notes.

What about BIM Execution Plans (BEPs) and Employer’s Information Requirements (EIRs)? “There are frameworks here but no good standardization. Each company has its own standard. In writing execution plans for our customers at Focus, I’ve developed a kind of low-end approach.”

Sandvik notes that advances in IT security in recent years, and particularly in the ability to ensure your data is stored in the EU, have made the use of cloud-based BIM systems viable in Norway. That in turn is encouraging attention to standards, he says, explaining that “when you use those kinds of systems, you need to have a very good standard and a very good execution plan.”

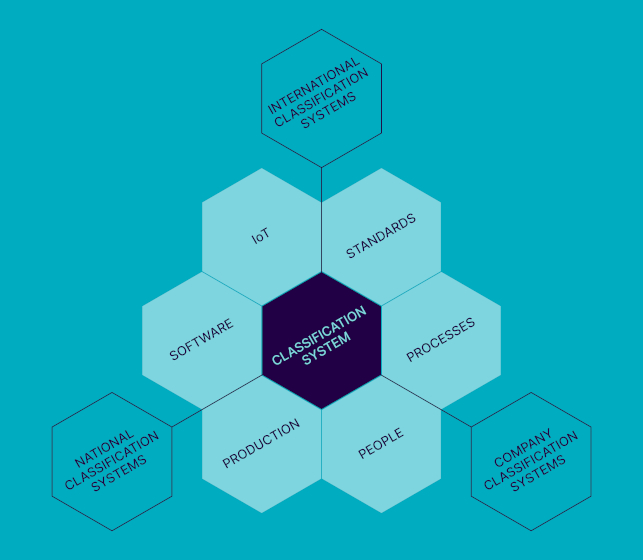

Classification culture in Norway

Norway has a long tradition of using AEC classification systems that dates back to at least the 1980s and has continually developed since then.

Statsbygg recommends its “interdisciplinary label system”, known as TFM (tverrfaglig merkesystem), which is used quite a lot in public buildings “to connect BIM models with facility management systems at the backend,” Sandvik says. He himself has been using a ‘dialect’ of the TFM classification system in his work on a new non-EU terminal at Oslo Gardermoen Airport.

There are other classifications too: Norwegian Standard 8360 is used to connect a model with cost-estimating products. (“It’s not widely used, but it is there.”) Then there is NS 3420, used to describe a building and project in detail.

“So you have two methods for description: a low-end one, just ‘this is a building and how much it costs’, and the high-end NS 3420 approach where each part in the model has a code,” Sandvik says.

Looking ahead, he sees a need for software that can connect multiple classification systems, like TFM, to multiple backend systems and models. “That type of middleware doesn’t exist now in Norway but will be needed in future. I know Agacad’s Classification tool can serve this purpose.”

Clear benefits of BIM

Years of widespread BIM use in Norway have made the method’s benefits clear. “Most of the time BIM does live up to the promises,” Sandvik says. “People here see that if you have detailed models of what you’re going to build, then there are fewer problems during construction. You can measure it and you find that that the number of problems at the building site really is less.”

That does not necessarily make everybody happy though, he notes: “Builders get paid to solve problems. If there are fewer problems, they get less pay. That can be a problem. Currently a kind of transition is underway in terms of how to estimate costs differently and reflect that in contracts.”

Thus Norway is adapting to the new reality of widespread digital construction.

Meanwhile, BIM adoption in the country continues. One driver is growing use of cloud-based “BIM 360” products from Autodesk and its competitors. Those products, which facilitate collaboration, “tend to draw all a project’s actors into the use of BIM tools and methods,” Sandvik explains.

That concludes our look at BIM today in Norway. Follow the Agacad blog for regular insights on BIM practices in different countries.

More Global BIM Survey reports are coming soon – stay tuned!

Prepared by Bryan Bradley of Textus Aptus